Two sides to two records – Wooy Midebar by Grammacks & Avispa by La Banda

The connections between Latin American and Caribbean music aren’t always obvious at first listen, but they’re undeniably there. The Caribbean has always been a region of movement and exchange – radio waves cross borders effortlessly, and historically, people traveled between islands and coastal areas for fishing, agriculture, and seasonal work, bringing their music with them. These constant migrations created a rich tapestry of sounds that share common influences while developing distinct local flavors. I discovered one of these hidden musical connections recently with “La Avispa,” a Costa Rican cumbia track by La Banda that I heard countless times growing up in Nicaragua, never knowing its true origins lay across the Caribbean in Dominica.

Discovering the Source

That cumbia classic “La Avispa” by Costa Rican group La Banda (1978) is actually a cover of “Wooy Midebar,” a cadence-lypso track recorded two years earlier by a band from Dominica called Grammacks.

I stumbled on this connection while researching La Banda online. Information about them is surprisingly scarce – I was just trying to learn more about the original band members (Ricardo Sáenz, Javier Cartín, Marco Monge, Alex Guerrero, Alexis Gamboa, and Carlos Berrocal) when I found mentions of “Wooy Midebar.” When I finally tracked down and heard the Grammacks version, I discovered not just the song’s origin but an entire genre I hadn’t known about – cadence-lypso.

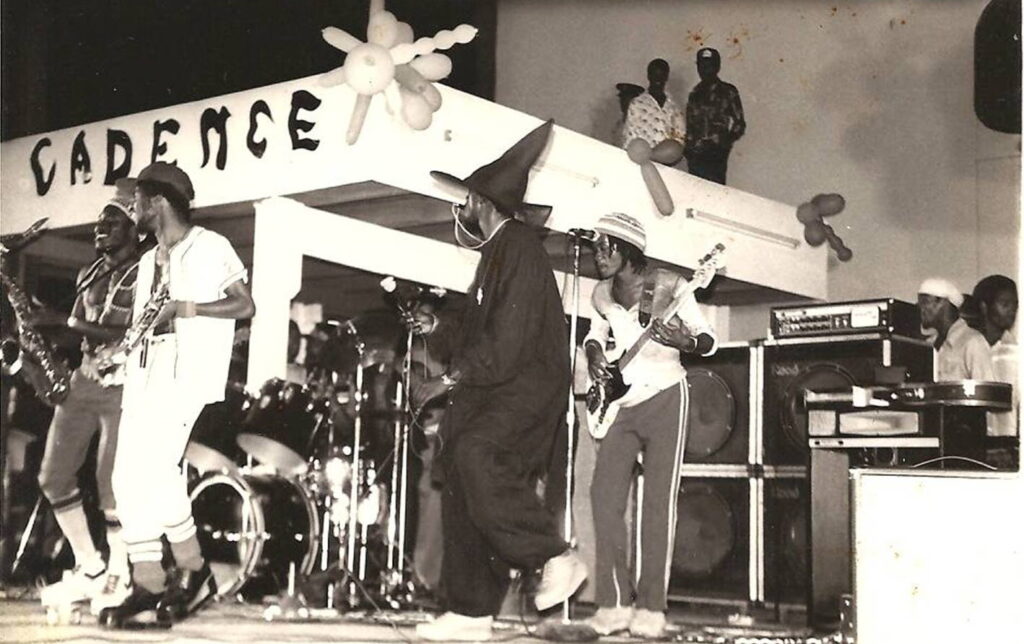

Cadence-lypso itself has a fascinating history – a genre pioneered in the 1970s by Gordon Henderson and his Dominican band Exile One. The style fused Haitian cadence rampa with elements of Jazz, Blues, and Trinidadian calypso. The genre quickly gained popularity throughout the Creole-speaking Caribbean, the French Antilles, and even parts of Africa. Grammacks, alongside Exile One, became one of the most important bands promoting this distinctive Caribbean sound.

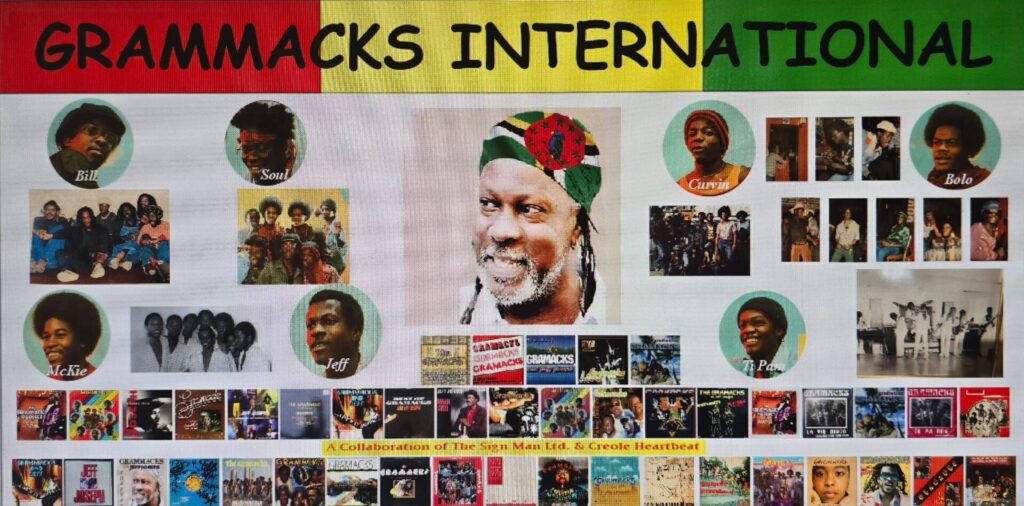

Grammacks formed in 1970 in the village of Saint-Joseph in Dominica, led by the charismatic vocalist Jeff Joseph. The band came together when a scheduled act from Roseau failed to show up for a village performance, prompting local musicians to create their own group. Despite initial struggles – including taking out loans to purchase instruments – they persevered and developed an impressive musical identity. Their lineup featured Anthony “Curvin” Serrant on lead guitar, Anthony “Tetam” George on bass, Elon “Bolo” Rodney on drums, and Mc Donald “McKie” Prosper on keyboards, with Georges “Soul” Thomas joining shortly thereafter.

From Dominica to Costa Rica

“Wooy Midebar” became their breakthrough hit in 1976, recorded during sessions in France. The song’s success led to them being invited to perform at stages of the Tour de France the following year.

La Banda recorded “La Avispa (Suavecito)” in 1978 on Indica SA, a Costa Rican label that was distributed by CBS. They wrote Spanish lyrics that mimicked the sound of the original Creole lyrics from the Grammacks version. Thanks to CBS’s extensive distribution network in Central America, this adaptation quickly reached Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, and Panama, becoming a regional staple.

While it’s unclear exactly how La Banda discovered “Wooy Midebar,” the Grammacks record was popular throughout the Caribbean in the mid-1970s. Whether through radio, travel, or record distribution, these musical exchanges were commonplace in an era when music traveled physically across borders through vinyl, cassettes, and live performances.

Personal Connections

I wrote about my experiences when I first was exposed to La Banda’s version of this classic in another post.

There’s something deeply poetic about how music travels. The journey from Dominica’s cadence-lypso to Costa Rica’s cumbia version wasn’t just a language change – it involved subtle shifts that made the song feel native to its new home. Yet the core of what made it special remained intact.

Musical Bridges Across Borders

Sadly, Jeff Joseph passed away in 2011 at just 57 years old. His cultural importance to Dominica was so significant that he received a state funeral. A billboard commemorating his achievements was unveiled last year.

Meanwhile, La Banda established themselves as Costa Rican legends, with “La Avispa” remaining one of their signature songs decades later.

Hearing both versions side by side reveals how remarkably different genres can interpret the same musical foundation. Grammacks’ cadence-lypso original pulses with Caribbean island rhythms, horn accents, and Creole vocal sensibilities, while La Banda’s cumbia adaptation shifts the entire feeling through Spanish lyrics, different percussion patterns, and Central American musical sensibilities. Interestingly, both versions rely on electronic synthesizer sounds for that signature buzzy lead that defines the song, and the laid-back cadence-lypso drums are rhythmically similar to the 70s cumbia patterns that were popular in Central America at that time. It’s the same musical skeleton dressed in entirely different cultural clothing, each version authentic to its regional context, yet sharing key sonic elements that made the adaptation work so seamlessly.

This connection between “Wooy Midebar” and “La Avispa” is just one thread in the vast tapestry of musical exchanges across the Caribbean and Latin America. From Jamaican ska influencing Panamanian music to Cuban son shaping Colombian cumbia, these regional cross-pollinations have created some of the world’s most vibrant fusion genres. For music lovers willing to dig beneath the surface, exploring these connections reveals how seemingly distinct traditions often share hidden musical conversations across borders, languages, and decades – making the exploration of Caribbean and Latin American music endlessly rewarding and full of surprising discoveries.